His father, a hosier, soon recognized his son's artistic talents and sent him to study at a drawing school when he was ten years old. At 14, William asked to be apprenticed to the engraver James Basire, under whose direction he further developed his innate skills. As a young man Blake worked as an engraver, illustrator, and drawing teacher, and met such artists as Henry Fuseli and John Flaxman, as well as Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose classicizing style he would later come to reject. Blake wrote poems during this time as well, and his first printed collection, an immature and rather derivative volume called Poetical Sketches, appeared in 1783. Songs of Innocence was published in 1789, followed by Songs of Experience in 1793 and a combined edition the next year bearing the title Songs of Innocence and Experience showing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul.

Blake's political radicalism intensified during the years leading up to the French Revolution. He began a seven-book poem about the Revolution, in fact, but it was either destroyed or never completed, and only the first book survives. He disapproved of Enlightenment rationalism, of institutionalized religion, and of the tradition of marriage in its conventional legal and social form (though he was married himself). His unorthodox religious thinking owes a debt to the Swedish philosopher

Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), whose influence is particularly evident in Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. In the 1790s and after, he shifted his poetic voice from the lyric to the prophetic mode, and wrote a series of long prophetic books, including Milton and Jerusalem. Linked together by an intricate mythology and symbolism of Blake's own creation, these books propound a revolutionary new social, intellectual, and ethical order.

Blake published almost all of his works himself, by an original process in which the poems were etched by hand, along with illustrations and decorative images, onto copper plates. These plates were inked to make prints, and the prints were then colored in with paint. This expensive and labor-intensive production method resulted in a quite limited circulation of Blake's poetry during his life. It has also posed a special set of challenges to scholars of Blake's work, which has interested both literary critics and art historians. Most students of Blake find it necessary to consider his graphic art and his writing together; certainly he himself thought of them as inseparable. During his own lifetime, Blake was a pronounced failure, and he harbored a good deal of resentment and anxiety about the public's apathy toward his work and about the financial straits in which he so regularly found himself. When his self-curated exhibition of his works met with financial failure in 1809, Blake sank into depression and withdrew into obscurity; he remained alienated for the rest of his life. His contemporaries saw him as something of an eccentric--as indeed he was. Suspended between the neoclassicism of the 18th century and the early phases of Romanticism, Blake belongs to no single poetic school or age. Only in the 20th century did wide audiences begin to acknowledge his profound originality and genius.

Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794) juxtapose the innocent, pastoral world of childhood against an adult world of corruption and repression; while such poems as "The Lamb" represent a meek virtue, poems like "The Tyger" exhibit opposing, darker forces. Thus the collection as a whole explores the value and limitations of two different perspectives on the world. Many of the poems fall into pairs, so that the same situation or problem is seen through the lens of innocence first and then experience. Blake does not identify himself wholly with either view; most of the poems are dramatic--that is, in the voice of a speaker other than the poet himself. Blake stands outside innocence and experience, in a distanced position from which he hopes to be able to recognize and correct the fallacies of both. In particular, he pits himself against despotic authority, restrictive morality, sexual repression, and institutionalized religion; his great insight is into the way these separate modes of control work together to squelch what is most holy in human beings.

The Songs of Innocence dramatize the naive hopes and fears that inform the lives of children and trace their transformation as the child grows into adulthood. Some of the poems are written from the perspective of children, while others are about children as seen from an adult perspective. Many of the poems draw attention to the positive aspects of natural human understanding prior to the corruption and distortion of experience. Others take a more critical stance toward innocent purity: for example, while Blake draws touching portraits of the emotional power of rudimentary Christian values, he also exposes--over the heads, as it were, of the innocent--Christianity's capacity for promoting injustice and cruelty.

The Songs of Experience work via parallels and contrasts to lament the ways in which the harsh experiences of adult life destroy what is good in innocence, while also articulating the weaknesses of the innocent perspective ("The Tyger," for example, attempts to account for real, negative forces in the universe, which innocence fails to confront). These latter poems treat sexual morality in terms of the repressive effects of jealousy, shame, and secrecy, all of which corrupt the ingenuousness of innocent love. With regard to religion, they are less concerned with the character of individual faith than with the institution of the Church, its role in politics, and its effects on society and the individual mind. Experience thus adds a layer to innocence that darkens its hopeful vision while compensating for some of its blindness.

The style of the Songs of Innocence and Experience is simple and direct, but the language and the rhythms are painstakingly crafted, and the ideas they explore are often deceptively complex. Many of the poems are narrative in style; others, like "The Sick Rose" and "The Divine Image," make their arguments through symbolism or by means of abstract concepts. Some of Blake's favorite rhetorical techniques are personification and the reworking of Biblical symbolism and language. Blake frequently employs the familiar meters of ballads, nursery rhymes, and hymns, applying them to his own, often unorthodox conceptions. This combination of the traditional with the unfamiliar is consonant with Blake's perpetual interest in reconsidering and reframing the assumptions of human thought and social behavior.

The Lamb"

Little Lamb who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee

Gave thee life & bid thee feed.

By the stream & o'er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing wooly bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice!

Little Lamb who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee

Little Lamb I'll tell thee,

Little Lamb I'll tell thee!

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb:

He is meek & he is mild,

He became a little child:

I a child & thou a lamb,

We are called by his name.

Little Lamb God bless thee.

Little Lamb God bless thee.

Summary

The poem begins with the question, "Little Lamb, who made thee?" The speaker, a child, asks the lamb about its origins: how it came into being, how it acquired its particular manner of feeding, its "clothing" of wool, its "tender voice." In the next stanza, the speaker attempts a riddling answer to his own question: the lamb was made by one who "calls himself a Lamb," one who resembles in his gentleness both the child and the lamb. The poem ends with the child bestowing a blessing on the lamb.

Form

"The Lamb" has two stanzas, each containing five rhymed couplets. Repetition in the first and last couplet of each stanza makes these lines into a refrain, and helps to give the poem its song-like quality. The flowing l's and soft vowel sounds contribute to this effect, and also suggest the bleating of a lamb or the lisping character of a child's chant.

Commentary

The poem is a child's song, in the form of a question and answer. The first stanza is rural and descriptive, while the second focuses on abstract spiritual matters and contains explanation and analogy. The child's question is both naive and profound. The question ("who made thee?") is a simple one, and yet the child is also tapping into the deep and timeless questions that all human beings have, about their own origins and the nature of creation. The poem's apostrophic form contributes to the effect of naiveté, since the situation of a child talking to an animal is a believable one, and not simply a literary contrivance. Yet by answering his own question, the child converts it into a rhetorical one, thus counteracting the initial spontaneous sense of the poem. The answer is presented as a puzzle or riddle, and even though it is an easy one--child's play--this also contributes to an underlying sense of ironic knowingness or artifice in the poem. The child's answer, however, reveals his confidence in his simple Christian faith and his innocent acceptance of its teachings.

The lamb of course symbolizes Jesus. The traditional image of Jesus as a lamb underscores the Christian values of gentleness, meekness, and peace. The image of the child is also associated with Jesus: in the Gospel, Jesus displays a special solicitude for children, and the Bible's depiction of Jesus in his childhood shows him as guileless and vulnerable. These are also the characteristics from which the child-speaker approaches the ideas of nature and of God. This poem, like many of the Songs of Innocence, accepts what Blake saw as the more positive aspects of conventional Christian belief. But it does not provide a completely adequate doctrine, because it fails to account for the presence of suffering and evil in the world. The pendant (or companion) poem to this one, found in the Songs of Experience, is "The Tyger"; taken together, the two poems give a perspective on religion that includes the good and clear as well as the terrible and inscrutable. These poems complement each other to produce a fuller account than either offers independently. They offer a good instance of how Blake himself stands somewhere outside the perspectives of innocence and experience he projects.

The Tyger"

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Summary

The poem begins with the speaker asking a fearsome tiger what kind of divine being could have created it: "What immortal hand or eye/ Could frame they fearful symmetry?" Each subsequent stanza contains further questions, all of which refine this first one. From what part of the cosmos could the tiger's fiery eyes have come, and who would have dared to handle that fire? What sort of physical presence, and what kind of dark craftsmanship, would have been required to "twist the sinews" of the tiger's heart? The speaker wonders how, once that horrible heart "began to beat," its creator would have had the courage to continue the job. Comparing the creator to a blacksmith, he ponders about the anvil and the furnace that the project would have required and the smith who could have wielded them. And when the job was done, the speaker wonders, how would the creator have felt? "Did he smile his work to see?" Could this possibly be the same being who made the lamb?

Form

The poem is comprised of six quatrains in rhymed couplets. The meter is regular and rhythmic, its hammering beat suggestive of the smithy that is the poem's central image. The simplicity and neat proportions of the poems form perfectly suit its regular structure, in which a string of questions all contribute to the articulation of a single, central idea.

Commentary

The opening question enacts what will be the single dramatic gesture of the poem, and each subsequent stanza elaborates on this conception. Blake is building on the conventional idea that nature, like a work of art, must in some way contain a reflection of its creator. The tiger is strikingly beautiful yet also horrific in its capacity for violence. What kind of a God, then, could or would design such a terrifying beast as the tiger? In more general terms, what does the undeniable existence of evil and violence in the world tell us about the nature of God, and what does it mean to live in a world where a being can at once contain both beauty and horror?

The tiger initially appears as a strikingly sensuous image. However, as the poem progresses, it takes on a symbolic character, and comes to embody the spiritual and moral problem the poem explores: perfectly beautiful and yet perfectly destructive, Blake's tiger becomes the symbolic center for an investigation into the presence of evil in the world. Since the tiger's remarkable nature exists both in physical and moral terms, the speaker's questions about its origin must also encompass both physical and moral dimensions. The poem's series of questions repeatedly ask what sort of physical creative capacity the "fearful symmetry" of the tiger bespeaks; assumedly only a very strong and powerful being could be capable of such a creation.

The smithy represents a traditional image of artistic creation; here Blake applies it to the divine creation of the natural world. The "forging" of the tiger suggests a very physical, laborious, and deliberate kind of making; it emphasizes the awesome physical presence of the tiger and precludes the idea that such a creation could have been in any way accidentally or haphazardly produced. It also continues from the first description of the tiger the imagery of fire with its simultaneous connotations of creation, purification, and destruction. The speaker stands in awe of the tiger as a sheer physical and aesthetic achievement, even as he recoils in horror from the moral implications of such a creation; for the poem addresses not only the question of who could make such a creature as the tiger, but who would perform this act. This is a question of creative responsibility and of will, and the poet carefully includes this moral question with the consideration of physical power. Note, in the third stanza, the parallelism of "shoulder" and "art," as well as the fact that it is not just the body but also the "heart" of the tiger that is being forged. The repeated use of word the "dare" to replace the "could" of the first stanza introduces a dimension of aspiration and willfulness into the sheer might of the creative act.

The reference to the lamb in the penultimate stanza reminds the reader that a tiger and a lamb have been created by the same God, and raises questions about the implications of this. It also invites a contrast between the perspectives of "experience" and "innocence" represented here and in the poem "The Lamb." "The Tyger" consists entirely of unanswered questions, and the poet leaves us to awe at the complexity of creation, the sheer magnitude of God's power, and the inscrutability of divine will. The perspective of experience in this poem involves a sophisticated acknowledgment of what is unexplainable in the universe, presenting evil as the prime example of something that cannot be denied, but will not withstand facile explanation, either. The open awe of "The Tyger" contrasts with the easy confidence, in "The Lamb," of a child's innocent faith in a benevolent universe.

London"

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every black'ning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But most thro' midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse

Summary

The speaker wanders through the streets of London and comments on his observations. He sees despair in the faces of the people he meets and hears fear and repression in their voices. The woeful cry of the chimney-sweeper stands as a chastisement to the Church, and the blood of a soldier stains the outer walls of the monarch's residence. The nighttime holds nothing more promising: the cursing of prostitutes corrupts the newborn infant and sullies the "Marriage hearse."

Form

The poem has four quatrains, with alternate lines rhyming. Repetition is the most striking formal feature of the poem, and it serves to emphasize the prevalence of the horrors the speaker describes.

Commentary

The opening image of wandering, the focus on sound, and the images of stains in this poem's first lines recall the Introduction to Songs of Innocence, but with a twist; we are now quite far from the piping, pastoral bard of the earlier poem: we are in the city. The poem's title denotes a specific geographic space, not the archetypal locales in which many of the other Songs are set. Everything in this urban space--even the natural River Thames--submits to being "charter'd," a term which combines mapping and legalism. Blake's repetition of this word (which he then tops with two repetitions of "mark" in the next two lines) reinforces the sense of stricture the speaker feels upon entering the city. It is as if language itself, the poet's medium, experiences a hemming-in, a restriction of resources. Blake's repetition, thudding and oppressive, reflects the suffocating atmosphere of the city. But words also undergo transformation within this repetition: thus "mark," between the third and fourth lines, changes from a verb to a pair of nouns--from an act of observation which leaves some room for imaginative elaboration, to an indelible imprint, branding the people's bodies regardless of the speaker's actions.

Ironically, the speaker's "meeting" with these marks represents the experience closest to a human encounter that the poem will offer the speaker. All the speaker's subjects--men, infants, chimney-sweeper, soldier, harlot--are known only through the traces they leave behind: the ubiquitous cries, the blood on the palace walls. Signs of human suffering abound, but a complete human form--the human form that Blake has used repeatedly in the Songs to personify and render natural phenomena--is lacking. In the third stanza the cry of the chimney-sweep and the sigh of the soldier metamorphose (almost mystically) into soot on church walls and blood on palace walls--but we never see the chimney-sweep or the soldier themselves. Likewise, institutions of power--the clergy, the government--are rendered by synecdoche, by mention of the places in which they reside. Indeed, it is crucial to Blake's commentary that neither the city's victims nor their oppressors ever appear in body: Blake does not simply blame a set of institutions or a system of enslavement for the city's woes; rather, the victims help to make their own "mind-forg'd manacles," more powerful than material chains could ever be.

The poem climaxes at the moment when the cycle of misery recommences, in the form of a new human being starting life: a baby is born into poverty, to a cursing, prostitute mother. Sexual and marital union--the place of possible regeneration and rebirth--are tainted by the blight of venereal disease. Thus Blake's final image is the "Marriage hearse," a vehicle in which love and desire combine with death and destruction.

Holy Thursday"

'Twas on a Holy Thursday their innocent faces clean

The children walking two & two in red & blue & green

Grey headed beadles walk'd before with wands as white as snow

Till into the high dome of Pauls they like Thames waters flow

O what a multitude they seem'd these flowers of London town

Seated in companies they sit with radiance all their own

The hum of multitudes was there but multitudes of lambs

Thousands of little boys & girls raising their innocent hands

Now like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song

Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of heaven among

Beneath them sit the aged men wise guardians of the poor

Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door

Summary

On Holy Thursday (Ascension Day), the clean-scrubbed charity-school children of London flow like a river toward St. Paul's Cathedral. Dressed in bright colors they march double-file, supervised by "gray headed beadles." Seated in the cathedral, the children form a vast and radiant multitude. They remind the speaker of a company of lambs sitting by the thousands and "raising their innocent hands" in prayer. Then they begin to sing, sounding like "a mighty wind" or "harmonious thunderings," while their guardians, "the aged men," stand by. The speaker, moved by the pathos of the vision of the children in church, urges the reader to remember that such urchins as these are actually angels of God.

Form

The poem has three stanzas, each containing two rhymed couplets. The lines are longer than is typical for Blake's Songs, and their extension suggests the train of children processing toward the cathedral, or the flowing river to which they are explicitly compared.

Commentary

The poem's dramatic setting refers to a traditional Charity School service at St. Paul's Cathedral on Ascension Day, celebrating the fortieth day after the resurrection of Christ. These Charity Schools were publicly funded institutions established to care for and educate the thousands of orphaned and abandoned children in London. The first stanza captures the movement of the children from the schools to the church, likening the lines of children to the Thames River, which flows through the heart of London: the children are carried along by the current of their innocent faith. In the second stanza, the metaphor for the children changes. First they become "flowers of London town." This comparison emphasizes their beauty and fragility; it undercuts the assumption that these destitute children are the city's refuse and burden, rendering them instead as London's fairest and finest. Next the children are described as resembling lambs in their innocence and meekness, as well as in the sound of their little voices. The image transforms the character of humming "multitudes," which might first have suggested a swarm or hoard of unsavory creatures, into something heavenly and sublime. The lamb metaphor links the children to Christ (whose symbol is the lamb) and reminds the reader of Jesus's special tenderness and care for children. As the children begin to sing in the third stanza, they are no longer just weak and mild; the strength of their combined voices raised toward God evokes something more powerful and puts them in direct contact with heaven. The simile for their song is first given as "a mighty wind" and then as "harmonious thunderings." The beadles, under whose authority the children live, are eclipsed in their aged pallor by the internal radiance of the children. In this heavenly moment the guardians, who are authority figures only in an earthly sense, sit "beneath" the children.

The final line advises compassion for the poor. The voice of the poem is neither Blake's nor a child's, but rather that of a sentimental observer whose sympathy enhances an already emotionally affecting scene. But the poem calls upon the reader to be more critical than the speaker is: we are asked to contemplate the true meaning of Christian pity, and to contrast the institutionalized charity of the schools with the love of which God--and innocent children--are capable. Moreover, the visual picture given in the first two stanzas contains a number of unsettling aspects: the mention of the children's clean faces suggests that they have been tidied up for this public occasion; that their usual state is quite different. The public display of love and charity conceals the cruelty to which impoverished children were often subjected. Moreover, the orderliness of the children's march and the ominous "wands" (or rods) of the beadles suggest rigidity, regimentation, and violent authority rather than charity and love. Lastly, the tempestuousness of the children's song, as the poem transitions from visual to aural imagery, carries a suggestion of divine wrath and vengeance.

The Nurse's Song"

When the voices of children are heard on the green

And laughing is heard on the hill,

My heart is at rest within my breast

And every thing else is still

Then come home my children, the sun is gone down

And the dews of night arise

Come come leave off play, and let us away

Till the morning appears in the skies

No no let us play, for it is yet day

And we cannot go to sleep

Besides in the sky, the little birds fly

And the hills are all cover'd with sheep

Well well go & play till the light fades away

And then go home to bed

The little ones leaped & shouted & laugh'd

And all the hills ecchoed

Summary

The scene of the poem features a group of children playing outside in the hills, while their nurse listens to them in contentment. As twilight begins to fall, she gently urges them to "leave off play" and retire to the house for the night. They ask to play on till bedtime, for as long as the light lasts. The nurse yields to their pleas, and the children shout and laugh with joy while the hills echo their gladness.

Form

The poem has four quatrains, rhymed ABCB and containing an internal rhyme in the third line of each verse.

Commentary

This is a poem of affinities and correspondences. There is no suggestion of alienation, either between children and adults or between man and nature, and even the dark certainty of nightfall is tempered by the promise of resuming play in the morning. The theme of the poem is the children's innocent and simple joy. Their happiness persists unabashed and uninhibited, and without shame the children plead for permission to continue in it. The sounds and games of the children harmonize with a busy world of sheep and birds. They think of themselves as part of nature, and cannot bear the thought of abandoning their play while birds and sheep still frolic in the sky and on the hills, for the children share the innocence and unselfconscious spontaneity of these natural creatures. They also approach the world with a cheerful optimism, focusing not on the impending nightfall but on the last drops of daylight that surely can be eked out of the evening.

A similar innocence characterizes the pleasure the adult nurse takes in watching her charges play. Their happiness inspires in her a feeling of peace, and their desire to prolong their own delight is one she readily indulges. She is a kind of angelic, guardian presence who, while standing apart from the children, supports rather than overshadows their innocence. As an adult, she is identified with "everything else" in nature; but while her inner repose does contrast with the children's exuberant delight, the difference does not constitute an antagonism. Rather, her tranquility resonates with the evening's natural stillness, and both seem to envelop the carefree children in a tender protection.

Holy Thursday"

Is this a holy thing to see,

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduced to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

Is that trembling cry a song?

Can it be a song of joy?

And so many children poor?

It is a land of poverty!

And their sun does never shine.

And their fields are bleak & bare.

And their ways are fill'd with thorns.

It is eternal winter there.

Summary

The poem begins with a series of questions: how holy is the sight of children living in misery in a prosperous country? Might the children's "cry," as they sit assembled in St. Paul's Cathedral on Holy Thursday, really be a song? "Can it be a song of joy?" The speaker's own answer is that the destitute existence of so many children impoverishes the country no matter how prosperous it may be in other ways: for these children the sun does not shine, the fields do not bear, all paths are thorny, and it is always winter.

Form

The four quatrains of this poem, which have four beats each and rhyme ABAB, are a variation on the ballad stanza.

Commentary

In the poem "Holy Thursday" from Songs of Innocence, Blake described the public appearance of charity school children in St. Paul's Cathedral on Ascension Day. In this "experienced" version, however, he critiques rather than praises the charity of the institutions responsible for hapless children. The speaker entertains questions about the children as victims of cruelty and injustice, some of which the earlier poem implied. The rhetorical technique of the poem is to pose a number of suspicious questions that receive indirect, yet quite censoriously toned answers. This is one of the poems in Songs of Innocence and Experience that best show Blake's incisiveness as a social critic.

In the first stanza, we learn that whatever care these children receive is minimal and grudgingly bestowed. The "cold and usurous hand" that feeds them is motivated more by self-interest than by love and pity. Moreover, this "hand" metonymically represents not just the daily guardians of the orphans, but the city of London as a whole: the entire city has a civic responsibility to these most helpless members of their society, yet it delegates or denies this obligation. Here the children must participate in a public display of joy that poorly reflects their actual circumstances, but serves rather to reinforce the self-righteous complacency of those who are supposed to care for them.

The song that had sounded so majestic in the Songs of Innocence shrivels, here, to a "trembling cry." In the first poem, the parade of children found natural symbolization in London's mighty river. Here, however, the children and the natural world conceptually connect via a strikingly different set of images: the failing crops and sunless fields symbolize the wasting of a nation's resources and the public's neglect of the future. The thorns, which line their paths, link their suffering to that of Christ. They live in an eternal winter, where they experience neither physical comfort nor the warmth of love. In the last stanza, prosperity is defined in its most rudimentary form: sun and rain and food are enough to sustain life, and social intervention into natural processes, which ought to improve on these basic necessities, in fact reduce people to poverty while others enjoy plenitude.

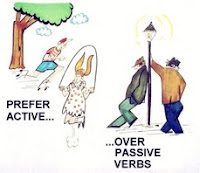

We find an overabundance of the passive voice in sentences created by self-protective business interests, magniloquent educators, and bombastic military writers (who must get weary of this accusation), who use the passive voice to avoid responsibility for actions taken. Thus "Cigarette ads were designed to appeal especially to children" places the burden on the ads — as opposed to "We designed the cigarette ads to appeal especially to children," in which "we" accepts responsibility. At a White House press briefing we might hear that "The President was advised that certain members of Congress were being audited" rather than "The Head of the Internal Revenue service advised the President that her agency was auditing certain members of Congress" because the passive construction avoids responsibility for advising and for auditing. One further caution about the passive voice: we should not mix active and passive constructions in the same sentence: "The executive committee approved the new policy, and the calendar for next year's meetings was revised" should be recast as "The executive committee approved the new policy and revised the calendar for next year's meeting."

We find an overabundance of the passive voice in sentences created by self-protective business interests, magniloquent educators, and bombastic military writers (who must get weary of this accusation), who use the passive voice to avoid responsibility for actions taken. Thus "Cigarette ads were designed to appeal especially to children" places the burden on the ads — as opposed to "We designed the cigarette ads to appeal especially to children," in which "we" accepts responsibility. At a White House press briefing we might hear that "The President was advised that certain members of Congress were being audited" rather than "The Head of the Internal Revenue service advised the President that her agency was auditing certain members of Congress" because the passive construction avoids responsibility for advising and for auditing. One further caution about the passive voice: we should not mix active and passive constructions in the same sentence: "The executive committee approved the new policy, and the calendar for next year's meetings was revised" should be recast as "The executive committee approved the new policy and revised the calendar for next year's meeting."